- Culture

- Film

- Features

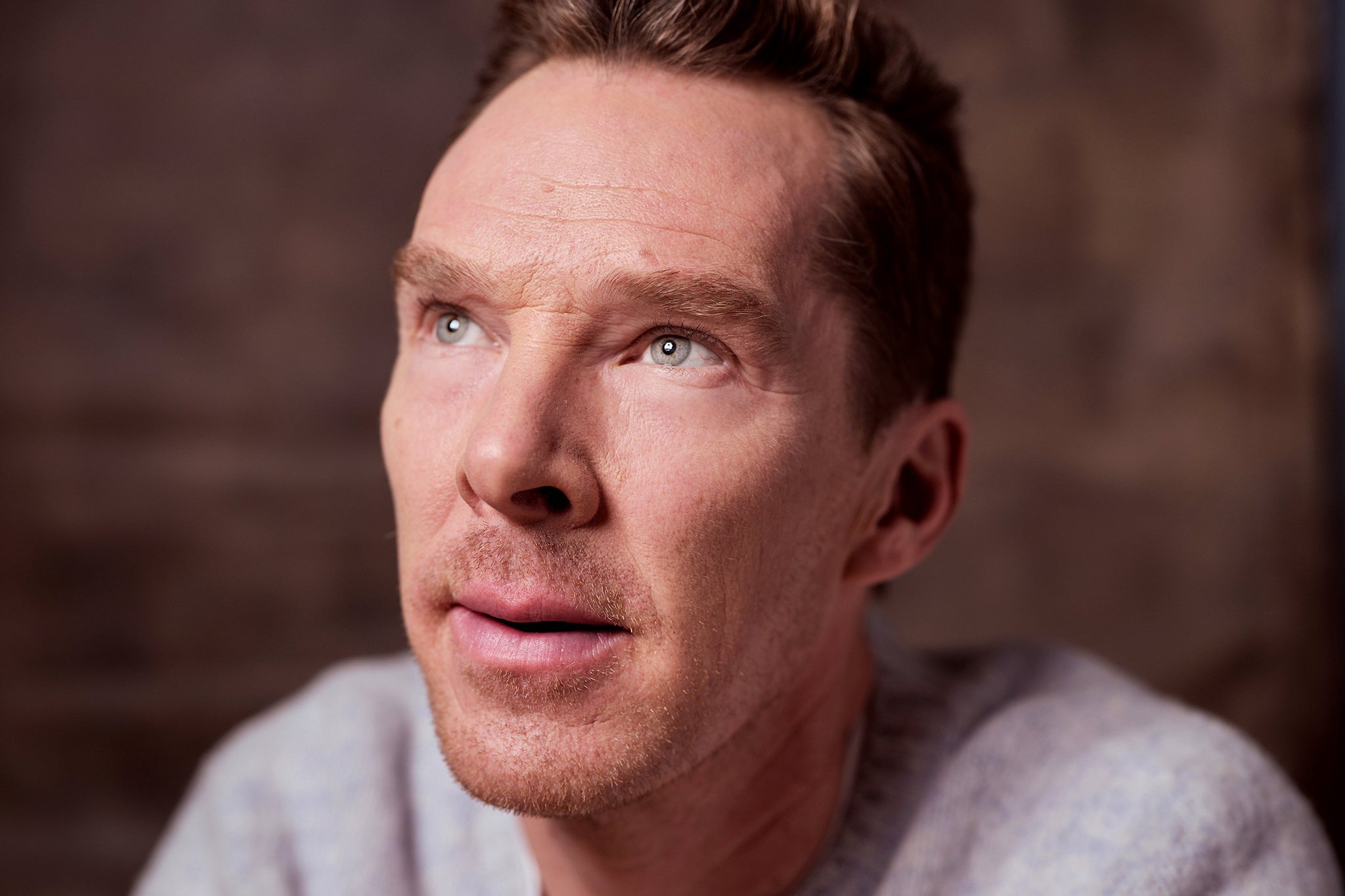

The Oscar-nominated star had to go deep for his role as a grieving father in the adaptation of Max Porter’s emotional bestseller ‘Grief is the Thing with Feathers’. He and Porter speak to Ellie Harrison about masculinity, raising sons, and how Cumberbatch is using his Marvel cachet to get films made that ‘struggle to exist’

Saturday 22 November 2025 06:00 GMTComments

Saturday 22 November 2025 06:00 GMTComments open image in gallery‘Media is co-opting children so early. And it is because of the devices we have in our hands’ (Jay L. Clendenin/Shutterstock)

open image in gallery‘Media is co-opting children so early. And it is because of the devices we have in our hands’ (Jay L. Clendenin/Shutterstock)

Get the latest entertainment news, reviews and star-studded interviews with our Independent Culture email

Get the latest entertainment news with our free Culture newsletter

Get the latest entertainment news with our free Culture newsletter

Email*SIGN UP

Email*SIGN UPI would like to be emailed about offers, events and updates from The Independent. Read our Privacy notice

For his new film The Thing with Feathers, Benedict Cumberbatch found a useful – if painful – shortcut to get him into the mindset of a bereaved man. In the adaptation of Max Porter’s luminous 2015 novel, Cumberbatch plays a father of two boys who is undone by grief after the sudden death of his wife. For one of the scenes, the child actors recorded a voiceover, where the boys open up about how much they miss their mother. Cumberbatch would listen to it when he needed to. “I used that as a device to put me into their pain, their perspective, their sense of loss,” he says. “And those innocent little voices talking about how their dad changed a lot after their mum died – ” he exhales sharply – “Immediate access to emotion there.”

That the actor has three sons of his own only compounded his sensitivity. “They say that the minute you have children, you become far more available emotionally, and everything’s a lot closer,” he says, touching the skin on his arm. “But, I mean, I’m nearly 50, so I’ve lived a bit. I’ve experienced grief. And anyone who’s loved or lost can tap into this film.”

At 114 pages, Porter’s original book is as light as, well, a feather. But within those pages is an experimental, poetic and emotionally bulky tale. A man and his sons are stumbling through their suffering when, all of a sudden, a talking crow crashes into their lives, uninvited, to serve as their “antagonist, trickster, healer, babysitter”. Porter, whose father died when he was just six years old, mined his own experience of losing a parent for the book. It is sometimes unbearably sad: “The whole place was heavy mourning, every surface dead Mum, every crayon, tractor, coat, welly, covered in a film of grief.” And often sad and funny at once: “People, on their last day on Earth, do not leave notes stuck to bottles of red wine saying ‘OH NO YOU DON’T COCK-CHEEK’. She was not busy dying… she was simply busy living, and then she was gone.”

In the film, adapted by Dylan Southern, Crow is voiced by David Thewlis (though sounds more like John Cooper Clarke) and depicted as a towering adult man in a bird costume. The creature, inspired by the crow figure in Ted Hughes’s poems, torments Cumberbatch’s character, known only as Dad, wherever he is – from the shower to the crisps aisle at the supermarket. When Dad is drinking and crying on the sofa, Crow berates him in tumbling, merciless dialogue: “Middle-age middle-class white widow music Guardian-reading beard-stroking farmer’s market guest ale Birkenstock Barbican s***! You’re such a cliche, you know? The dead wife trope. You’ll have the photo album out next, you’ll be talking to her headstone.” It’s tough love.

If your head is spinning from this description of the film, it should come as no surprise that Porter’s novel – a freewheeling and often disorientating triptych story that hops between the perspectives of Crow, Dad and Boys – was largely seen as unadaptable at first. “Dylan read it and thought, ‘Wow, that would be unfilmable,’” says Cumberbatch, “and then within two weeks was pitching to Max in a coffee shop and won the rights to develop it.”

Benedict CumberbatchChildren have an extraordinary ability to be empaths without any lived experience

Cumberbatch and Porter, whom I meet in a London hotel, are sitting side by side on a sofa. Porter leans back, legs crossed, his voice deep and relaxed. Cumberbatch is pitched forward, on the edge of his seat, all go. It is the end of a long press day, so they are a slightly unruly pair. Cumberbatch is wearing a bright green jumper with two slits across the chest. He proudly demonstrates that this is a fun jumper, one where he can pull tufts of yellow material out of the two openings. “Nipple hankies!” he declares, ecstatic, before pretending to dab away tears with the fabric. It sets the tone for an unwieldy conversation, with the pair coming across like brothers, their conversation swinging from the heaviness of The Thing with Feathers to how they like their tea to the time Porter wept on a plane while watching Aquaman.

“The book was actually deemed unpublishable,” says Porter. “The first ever email I got back from a colleague at Faber [the publishing house he worked at] said, ‘Tell him to go and write a proper one.’” Now, 10 years on, it has been adapted numerous times (including into a play starring Cillian Murphy), translated into 38 languages, and Dua Lipa is a superfan. The book’s success, admits Porter, has been “surreal” for him to witness, as well as “gladdening and massively, life-affirmingly trippy and wonderful”. He found it especially strange being on the set of Southern’s film. “It looked uncannily close to my dad’s flat, so that was the first time I’ve been like, ‘Dad, if you can hear me, I’m sorry, this is weird. I perhaps should have run this by you.’”

Porter believes that people connect with the tale because it doesn’t give Dad a backstory or include the mother’s voice, and therefore has an “emptiness that people can pour themselves into”. “A friend of mine last year lost his wife, and has two young sons,” he says. “We went for a walk because he’d read the book and he wanted to talk about how right I’d got it, and it felt horrible for me to be saying, ‘Thank you and sorry and f***,’ you know?’ But if I had turned it into a more conventional novel and padded out some of the empty space, it wouldn’t have been a collaborative gesture, and it wouldn’t have felt to the reader like it’s your flat, your relationship, your grief.”

open image in galleryCumberbatch gives a raw performance as a bereaved husband in ‘The Thing with Feathers’ (Vue Lumière)

open image in galleryCumberbatch gives a raw performance as a bereaved husband in ‘The Thing with Feathers’ (Vue Lumière)While Porter and Southern have been working on the film on and off for a decade, Cumberbatch came on board only about a year and a half ago. It is co-produced by the actor’s company SunnyMarch, and a world away from his mega-budget Hollywood staples such as Doctor Strange and The Power of the Dog, in both its scale and the rawness of Cumberbatch’s performance. “I’m trying to use the currency that I’ve been gifted – through fantastic, tentpole, spectacular fare – to shine a light on filmmaking that struggles to exist,” he says.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for freeADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for freeADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

One particular aspect of The Thing with Feathers that drew Cumberbatch in, and made him feel like it was a story to tell now, was Dad’s struggle to cope with his overwhelming sorrow. He tries to hide his grief from the boys, so instead it comes out in rageful fits as he screams at them over breakfast. At other points, he is entirely bottled up, wincing at his despairing reflection in the bathroom mirror.

“I think it’s really important to have the conversation around the male inability to manage emotion,” says Cumberbatch, “and how easily co-opted it is into pretty awful causes, whether it be incel culture, riot culture, or blame culture – where your problem is not your problem, it’s that person’s over there. I think it’s so important to realise, ‘No, it’s OK, you can take responsibility, you can also be a mess, you can also be vulnerable to human emotions, and you can feel stuff at a very profound level.’ This is all there in this film. And it’s also about the mess that men make of their lives without women.”

What is refreshing to see in The Thing with Feathers is just how kind and good the little boys are. Under 10, they’re at an age where they’ve not yet been properly exposed to the adult world and social media. “Media is co-opting children so early,” says Cumberbatch. “And it is because of the devices we have in our hands. We have to control the access that they provide to all of us. We can’t just go, ‘Well, let’s give a smartphone to our kids and see what happens.’ Look what’s happened to an entire generation.”

open image in galleryPorter (left) and Cumberbatch with child actors Henry and Richard Boxall, and director Dylan Southern, at the London Film Festival (Getty)

open image in galleryPorter (left) and Cumberbatch with child actors Henry and Richard Boxall, and director Dylan Southern, at the London Film Festival (Getty)As a father, Cumberbatch has found it deeply moving to see his own small boys, unburdened by the world’s ills, being naturally loving and compassionate. It echoes a passage in the book where Dad says that “the pain of them being so naturally kind is like appendicitis”. Cumberbatch nods vigorously as I read it out. “Children have an extraordinary ability to be empaths without any lived experience or promptings,” he says, and then gestures to Porter, who also has three sons. “We’ve both experienced that as dads. They just go to you and give you love, unasked for, and it’s regenerated, without any input or feedback from you, necessarily, to bolster that.”

Porter agrees. He’s on the edge of his seat now, too. “I’m always saying to my kids, ‘Hurry up! Do your homework! Be kind!’ And then when you least expect it, bang! There it is. It’s beautiful.”

They glance at one another, smiling. “It makes you excited to be alive, sometimes.”

‘The Thing with Feathers’ is in cinemas

More about

Benedict CumberbatchMax PorterJoin our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments